Changes of Biblical Proportion

Remember the good old days, when “Timber was King”?

There was a broad, diverse, healthy and competitive market for timber products. For decades, timber prices were strong and rising. Clients were confident, even enthusiastic, about spending money on reforestation in anticipation of solid, competitive financial returns and revenue. Every raindrop grew a sheet of paper and a pot of gold was at the end of every rainbow! Consulting businesses were thriving, and the number of consultants was increasing. Timber was King!

Today, the South’s forestry community has changed. Free market influences that produced an abundance of timber and a profitable enterprise for growers have diminished significantly … at least for a time. Reforestation over the past few decades, increasing sawmill efficiencies and government sponsored reforestation programs have created a surplus of timber. In addition, the forest industry has been consolidating and repositioning.

Each mill now dominates in their respective region. There is less competition.

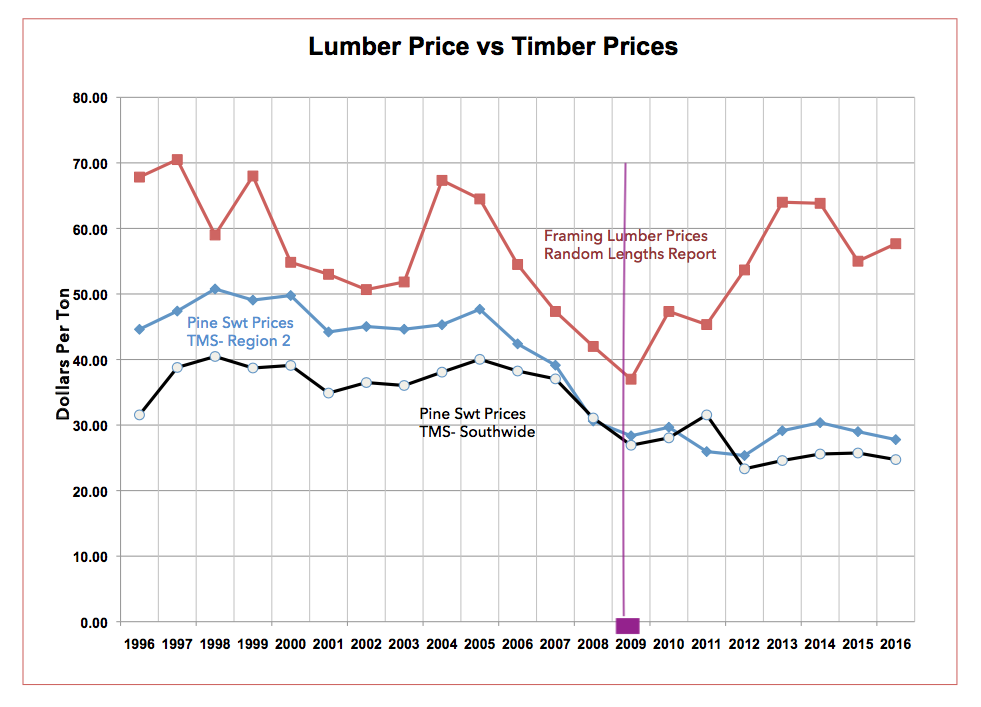

Today, a landowner’s average timber revenue is 50 to 70% less than received 20 years ago. The housing collapse drove lumber prices down, and along with it came lower timber prices. Interestingly, lumber prices increased in 2009 and continued to trend upward while delivered log prices either remain at 2009 levels or declined.

There is now a complete disconnect between lumber prices and log prices. This has never happened in modern times. The natural and historical landowner reaction to such price behavior is to withhold timber from the market until prices “return to normal.”

Over the past eight years, the disconnect between sawlog prices and lumber prices remains and will likely continue for an indefinite time. We seem to be living in a new “normal”. What the heck is going on?

Let’s take a glimpse at the past 50 years. While history may not be a predictor, when combined with some economic principles, it will help us understand the future of our forestry community.

The Promised Land: A Land of Milk and Honey … 1970-1990

The timber industry was expanding. The development of new glues and processes brought southern pine plywood into being and opened new markets for timber. Family-owned mills remodeled and increased capacity, and the demand for timber increased. Small log processing technology emerged, calling itself Chip-N- Saw, a process that generated lumber plus chips for expanding paper mills. Prices for all forest products were rising and whole tree logging and better mill utilization left less waste and contributed to lower reforestation cost.

Private non-industrial landowners responded and began planting more trees. Genetic research increased the quality of trees that grew faster, straighter, and more resistant to disease than ever, thereby increasing lumber outturn from the same load of logs. Herbicides replaced bulldozers for site preparation, leaving fragile topsoil intact. Domestic consumption of forest products increased. Export and import of forest products increased. Times were good. The free market economy was thriving and rewarding to growers, foresters and processors alike.

During the latter half of this period, pulp and paper mills came under pressure from Wall Street to separate their timberland holdings from manufacturing. Paper companies were seen as good manufacturers, but not so efficient at maximizing returns from their forest. Therefore, pulp and paper manufacturers were encouraged to divest of their timberland. This allowed for these properties to be acquired more efficient, investment-minded owners that focused on maximize timber production and returns. Hence, the Timberland Management Organization (TIMO) was born in the mid 1980s.

In the first few years, the first Timberland Management Organizations were met with limited success, but they continued to educate potential investors (mostly pension funds). Slowly but surely, investment capital began to flow into timberland.

Timber Kings grow crops for the multitudes … 1990-2000

Bowing to the pressure from Wall Street to sell, forest products companies, with approximately 20% of the South’s productive timberland, began offering lands for sale. TIMO’s with bundles of pension fund cash were ready buyers. By the end of the 1990s, a considerable portion of industrial lands were owned by investors, mostly large pension funds. Eventually publicly traded Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT’s) also emerged to serve the average investor, who wanted to own interest in timberland without taking on the management responsibility required by outright fee simple purchases.

Competition for timber (sawlog and pulpwood) came from a broad and stable market of private, family-owned mills and large, publicly-owned mills. Competition for timber in some market areas was fierce, yielding 10 to 15 bids for a single timber sale offering. Opening of bids practically became a social occasion. Timber prices continued to rise. Timberland owners were happy and experienced increasing revenue and returns on their investment. With the prospects of a bright future in growing timber, tree planting increased, and cultural practices became more intense and frequent. Market incentives were working to produce more and more timber. Also, government programs with “free money” encouraged even more planting on wild lands as well as surplus cropland.

Markets for fuel wood expanded in the form of chips as well as pellets for export and domestic use. Computerized technology improved sawmill’s production and efficiencies, resulting in the production of more lumber from the same log.

Pulp and paper company forests, once managed on a short rotation to produce a high component of pulpwood, were now owned and managed by investors and their advisors. Along with the change in ownership came a change in forest management strategy … a shift to longer sawtimber rotations. This resulted in a big shift in management strategy for 20% of the most productive lands in the south. A wall of sawtimber was quietly in the making but still far below the horizon.

By the late 1990s, timber prices, particularly sawlog prices, were at an all-time high across the south.

Charioted warriors storm the kingdom: Year 2000 to Today

During the early part of the new century, pulp and paper mills continued to divest of their timberland, and institutional investors continued to buy it. Eventually, pulp and paper mills became exclusively manufacturers. At the same time, another huge change was quietly occurring. No longer bound to the geographic region of their timberland base, mills began restructuring and repositioning for the future.

Forest products companies were selling mills here and buying mills there, positioning themselves for a future that would result in less competition and lower wood cost for their mills within its respective geographic wood basket. During this period the housing bubble burst, sending real estate prices spiraling downward, and soon followed by lumber and timber prices.

During the economic depression, many small, less efficient family-owned mills closed while larger, more modern mills were sold. Georgia mills sold mostly to Canadian sawmill operators — with one Canadian company owing seven mills in Georgia. Their Canadian cousin eventually purchased six more sawmills in the region. Mills that once competed with one another for sawlogs were now owned by just a few sawmill operators.

As competition declined, so did timber prices, notwithstanding the rise of lumber prices. In Georgia, sawtimber that sold for as much as $70 per ton in the late 1990s, now sells at 50% to 70% less. At the same time, more restrictive log specifications have effectively further reduced prices.

Reflecting on the Events

Looking back, foresters have done a tremendous job of growing trees. Some might say too good! We now have a huge surplus of wood, with surplus estimated to last at least 20 years, based on current production.

Remember Economics 101? Scarcity creates value. Timber is no longer a scarce commodity, and timber prices reflect that fact. According to a recent timber supply report, the surplus will continue to build over the next 20 years, assuming existing mills continue to run at or near capacity.

Today, sawmill operators have acquired, consolidated, or repositioned so that their mills dominate a respective timber supply area. By design or happenstance, there is little or no competition for sawlogs in many areas of Georgia. The major sawmills set the price and the smaller operators (if they exist) follow their lead. Competitive bidding for a timber sale is essentially a thing of the past!

Domestic mills have repositioned, and Canadian sawmill companies have moved into the South and geographically dominate their local wood baskets. Effectively, mills have created a dominant position where they control and pay as little as possible for logs and sell lumber at a high-as-possible price. That’s the American way. No wonder these foreign businesses love it in America!

In the past, landowners participated in the market where timber prices closely tracked the ebb and flow of lumber prices. Today, this relationship no longer exists. With little or no competition, landowner’s timber prices are now set by the mill.

How has this happened? The “wall of wood” is now above the horizon, and timber supply far exceeds the demand.

What has been the landowner’s reaction? There has been a growing reluctance in the private sector to spend money for intensive culture and expensive reforestation in the face of today’s low timber prices and monopolistic timber sale environment.

In regions where sawlog prices are low and pulpwood prices are still somewhat competitive, landowners are planning for shorter pulpwood rotations. Meanwhile, government continues to feed tax subsidies to landowners to encourage more tree planting. This ill-advised, non-market influence to plant more trees will further exacerbate the oversupply problem.

As often referenced, “If you continue to do the same thing, you will continue to get the same results.” It is clear the result is an oversupply of timber.

The future and beyond: Searching for a savior

What will happen in the future? If we believe in the free market system, then we must also believe that a surplus timber supply will attract new forest product industries, or that existing mills will substantially increase production, or possibly both. This will eventually reduce the surplus, increase competition, and cause sawlog prices to rise to a profitable and sustainable level for both growers and processors. With all the variables, one thing is certain — the absence of competitive financial returns will lead to less investment and less forest management which will result in less timber production.

Price is the great sustainer, the great negotiator. Price balances supply and demand.

Enthusiasm for timberland investment has and will continue to decline, for a time. Money follows opportunity, and if timber is no longer viewed as a profitable opportunity, money will naturally flow to alternative investments. This is especially true for the new “investor class” (TIMOs) that currently owns/manages approximately 20% of the south’s most productive timberlands.

Large landowners, who have historically been driven by timber revenue, may not get out of the business. However, they will change their management strategy by reducing forest management expenditure (less intensive cultural practices), altering rotation lengths and targeting specific product objectives.

At some point in the next 20 to 30 years, “Ole’ Man Scarcity” will again appear, and timber prices will rise. If you are under 60 years old, you may witness this event. If you are over 60, maybe your children will “drone” you over to watch a harvest that has returned to profitability.

No, I’m not a prophet but I do believe that history is a good teacher. In a free market economy, economic principles are like gospel.